Collections

News

News

S.W.A.T. MAGAZINE – KEEP YOUR CARBINE RUNNING

Dispelling Lubrication and Cleaning Myths

I grew up at a time when most every male had seen some military service, and I was treated to numerous tales of life in the service of this country in combat and in peacetime.

That exposure, and a strong desire to get out of the city and actually do something that mattered, led me to enlist in the Marine Corps shortly after my 17th birthday.

While I had fired rifles and pistols before, my education was informal and generally limited to what my Dad and others remembered, as well as the articles in the various gun-related magazines of the time. Cleaning was something that took on an almost formal overtone and was continued for three consecutive days.

This paled in comparison to what I was taught in the Marine Corps Recruiting Depot (MCRD), where cleaning was in fact a religion, and reached Jesuitical proportions at Parris Island. The brand-new M14s were scrupulously scrubbed on that three-day schedule, a remnant of the use of corrosive primers during World War II. No one had bothered to tell the Marine Corps that that was then, and this was now, so three consecutive days it was. Interspersed with the cleaning lectures were equally ardent lectures about why we shouldn’t believe all of the gun magazines and newspaper articles bemoaning the adoption of the M14 and how this monstrosity would lead to the demise of the Western World.

Surprisingly, when we got to the Infantry Training Regiment (ITR) at Camp Geiger, we were issued M1 Rifles, and all of the T/E equipment was what we would now consider old school-M1918A2s, M1919A4s, etc. The training schedule was all field oriented and we shot what was considered a lot (by 1963 standards). On several occasions after returning late from the cold and wet North Carolina training sites, I marched my squad straight into the shower. We scrubbed the mud off our rifles, 782 Gear and bodies. We brought the rifles into the squad bay and briefly cleaned and lubed them on the deck while using the miniscule cleaning gear that we were issued or purchased. We squared our gear away and grabbed a few hours sleep before heading off to learn something new about killing other humans.

What a great life!

I was initially terrified that we weren’t spending enough time cleaning those old M1s, but they continued to work as long as they were properly lubed and moderately cleaned. Then I began worrying that the M14s might be more fragile if they required such constant attention as taught at MCRD. How could that be? After all, they were similar in many respects, so why did one require much more cleaning than the other?

The short answer is that they don’t require a different cleaning regimen because they are different rifles-it is just that cleaning has to be looked at from several widely divergent points of view.

The first and most obvious is that, if there is sufficient time available for cleaning, that time will be used for cleaning, meaningless or not. Second is that, under exigent circumstances, a quick cleaning, paying particular attention to salient points, may be all that is necessary to keep the weapon running.

A military issue is that in many units the armorers-and sometimes even an officer-will conduct what amounts to a “white glove” inspection, wherein the troops will be kept “busy” by performing useless, and sometimes harmful, “cleaning” in order to satisfy the whims of despots and buffoons. Removing protective lubrication or scraping away finish does nothing to improve serviceability-it only destroys the guns and angers the troops.

When the M16 first came upon the scene (shortly after the M14), it was a shock to those who believed in wooden stocks, match sights and big bullets. It was billed as needing minimal cleaning, which turned into self-cleaning, which turned into no cleaning as some rifles were issued “in country” without cleaning equipment. Several issues combined to make a tolerance stack, and malfunctioning rifles were the result.

Probably as the result of these issues in the late 1960s, a myth of grand proportions has swelled up concerning the care and cleaning of the AR platform. This myth specifies that the AR must be kept spotlessly clean, and that it takes an hour (if not more) of steady cleaning for the rifle to be once more useful. Indeed, because this rifle allegedly dirties where it feeds, it must be cleaned regularly and with great care if you are to use it. Also, a few meager grains of sand will cause it to stop running.

The highlight for many errornet pundits comes when then rally around a female soldier whose convoy was ambushed during Operation Iraqi Freedom. “Remember Jessica Lynch” has become a cry of the unknowing, and while the subject makes for great points for their side, it is flawed.

Reports concerning this incident state that there were weapons malfunctions to be sure. However, a sergeant in that convoy stated that the weapons were cleaned daily and were clean when they left that morning. The M16A2 wielded very efficiently by a soldier who killed six of the enemies with it did malfunction-because of a faulty magazine and a broken extractor. This is a service-life issue with the rifle, not a design flaw. While leadership and depot level maintenance might have prevented something like this, the proper steps were not taken at a level above the soldier in the field. An M249 also failed, but that may have been due to lack of training with the weapon. And what of the celebrated centerpiece of this fight? She may have been knocked unconscious when her vehicle crashed at the beginning of the action-but this is casually brushed aside in the bubble gum (gun) forums. The serviceability of her weapon is therefore moot.

Here’s a news flash: Sand in the chamber will stop most guns-M16s, AK-47s, M24s, M1s, M9s and so forth. It is not unique to the AR platform.

Cleaning is a hot-button topic, and a great many (especially AR detractors) really believe that the AR has to be kept meticulously clean to function. While having a clean gun is never bad, neither do you have to put up with the white glove nonsense.

My cleaning regimen may be different from conventional protocol, but it works and has stood the test of time. I normally spend no more than ten minutes doing a field cleaning, and oftentimes less than that. If it takes you an hour, you are wasting time on something or you are doing something wrong.

This is the cleaning protocol that I use. This isn’t “the” way, but rather “a” way. I don’t pretend to know everything, and I wind up learning something new almost every day. Not using what is listed below won’t necessarily get you killed, make you unattractive to a potential mate nor make you unpopular at the local gin mill.

I’ll field strip the carbine and punch the tube with a wet patch. Leave the chemicals to do their work and get to the bolt/bolt carrier assemblies.

Spray the bolt with either Slip 725 or Evinrude Johnson Engine Turner and let it sit.

Clean the bolt carrier assembly by removing carbon from the bolt carrier (yeah, that chrome-lined thing where the bolt goes in) and the bottom of the bolt carrier itself. You can use a wet pipe cleaner to clean the inside of the bolt carrier key, but I rarely do. Do not put anything inside of the gas tube-it is unnecessary, and you will only stick debris in there that can do no good.

Use your toothbrush and a rag to clean the bolt, specifically the bolt lugs. Do not concern yourself with the carbon build up on the bolt’s tail. No matter how you clean it, it will just reappear the next time you shoot it. I had an armorer once tell me that the carbon promoted corrosion. That may well be if the gun is never shot, but I have yet to see a working bolt corrode away.

Attach the chamber brush to your cleaning rod and scrub out the chamber. I generally use a worn brush, wrap a wet patch around it and insert it in the chamber. Spin it a few times and replace it with a fresh brush and patch. Spin that and then dry the chamber out. Clean out the locking lugs with cotton swabs.

Spray some Slip 725 into the upper receiver and the charging handle. Your toothbrush and cotton swabs work well here.

Take a few dry patches and clean the barrel. Note that I don’t normally use a bore brush, and allow the cleaning fluid to take care of the bore.

Before the rockets start flying, let me state that I used to shoot Service Rifle, and am a High Master and a Distinguished Rifleman. I rarely used a brush on my M14NM or match AR-15s. If I felt that the bore was heavily fouled, I ran several wet patches through it, and if I absolutely felt the need for a brush, it was nylon, not copper. Never ever use a stainless steel brush in your barrel.

Understand that this is for a carbine, which by virtue of its definition is a short-barreled rifle. The 5.56x45mm service rounds and M4 carbines are certainly capable of hitting out past 500 meters, but it shines in fights that take place under 200 meters. Bothering with inconsequential increments may not be useful under these circumstances. However, if you have an SPR type, by all means give the care to that barrel that it deserves, but that care may be wasted on a 10.5-inch to 14.5-inch carbine.

Before reassembling, check your bolt rings for serviceability. Insert the bolt into the bolt carrier, and turn it upside down (preferably over something soft). If the bolt falls out on its own, you need to change the gas rings. If not, you are good to go.

Don’t get locked into the nonsense of misaligning the gas rings. The Colt Armorer instructors state emphatically that the gun will run with only one good ring, and I have done exactly that. We have been teaching that misaligning the gas rings is a waste of time for about ten years or so. I have seen nothing that leads me to believe differently.

One of the very prominent AR myths is that the gun runs better dry. It is a myth.

The AR series runs significantly better wet than dry, but there are those who approach this with such great trepidation that they steadfastly refuse to use only a tiny bit of lube on their carbines, causing them to cease functioning after a very short while.

Hundreds of e-net posts speak of using little lube on the carbines, believing that too much lube is the cause of all problems. A friend, a retired Marine MSgt and a prolific Class 3 collector, looks at lube like it was two-day old cat urine, and is absolutely phobic about putting anything more than a drop or two on any gun.

Our experience is that, after poor magazines and operator-induced malfunctions, dry guns are a major cause of stoppages. We see this in every class we have ever attended or taught, and we are satisfied that our observations regarding lubrication are correct.

Consider that your carbine is a machine, and like an internal combustion engine, it requires lubrication to make it function. There are certain wear points in the gun that need attention, and failure to do so can cause a stoppage. A good rule of thumb is to look for shiny marks, which indicate metal-to-metal contact. If it shines, get it wet.

Remove the bolt from the bolt carrier. Turn the bolt carrier over and observe the shiny area on the bottom. This is a wear point. The slot that the bolt cam pin rides in is another wear point, as is the chromed hole in the bolt carrier that the bolt rides in. The entire bolt carrier can use a coat of lube, but pay particular attention to those areas. The military also states that a drop down the bolt carrier gas key is required.

The bolt itself requires a coating of oil, paying particular attention to the bolt rings and the lugs. Those bolt rings function just like the piston rings in your car engine. How long do you think your ride would last without lube?

A properly cleaned and lubed carbine should go a minimum of 500 rounds to 1000 rounds without any cleaning at all. However, using a suppressor will cut that number down drastically, as will firing multiple rapid-fire strings or firing with the selector switch on “Group Therapy.”

I advise shooters that during the chow break they should place a few drops of oil into those two gas ports on the right side of the bolt carrier. The lube will get into the gas rings located handily nearby and keep your gun running smoothly.

Finally, a few drops of oil into the underside of the charging handle are not a bad thing.

The AR system runs much better wet than dry, and we see that during every class.

Understand that it is not the amount of lube used, but also the placement of the lube. At one class, a very experienced shooter was having functioning problems. He pulled back on the charging handle to show me that the bolt was wet, but when he released the charging handle, I could see that the area on the bolt carrier adjacent to the gas holes was dry. I placed two drops of Slip 2000 into those holes and the gun ran fine.

The moral of this story is not just to put lube on, but put it on in the right places.

Keep in mind that when at class and shooting 400-1000 rounds per day, the bolt will get blown dry. Adding oil during break time will keep the gun running and keep you learning new skill sets instead of becoming frustrated with a constantly malfunctioning gun.

In the 1990s I worked for a government agency that had a large budget. We had a fair number of guns and a lot of ammunition, so on the down days I had the opportunity to play and run some informal tests. While the exact results have been lost to the ages, some salient points remain embedded in my brain-housing group.

A totally dry gun will run approximately 100-200 rounds before seeing problems.

A clean, properly lubed gun in good condition should go from 500 minimum to 1,100 maximum.

More lube is not necessarily bad. I submerged bolt and bolt carrier assembly into a bucket of oil, shook it off and placed it into the carbine. It ran like a clock, though I only had enough time to fire off four mags worth of M855 through it.

I have used every type of lube imaginable, going from WD-40 (especially good when you have a dirty gun), to 3 in 1 oil, suntan lotion, butter and even Vagisil-don’t laugh, it works.

I may not want to use any of them for the long haul, but for a quick fix, it beats having a non-functioning gun.

The type of lube you use is something else that is full of mythology and sprinkled with fact. While the military uses CLP, a book several years ago cautioned against using it for cleaning as it “promotes carbon.” Why it only promotes carbon for cleaning and not lubricating is a mystery to me, but I don’t use CLP for anything anymore.

Commercial choices abound, from mystical concoctions of “Sergeant Major’s brew” to a host of “this is the best stuff ever made and we’ll sue anyone who says different” crap.

I prefer to stay away from most petroleum-based products, and use Slip 2000 for lube and that same company’s 725 Cleaner and Degreaser for the other chores. Slip 2000 is aqueous based, eliminating a lot of the contamination issues seen with petroleum products, and their products flat work. I have found Slip 2000 to be excellent and the owner, Greg Connor, is a great American.

If I need grease, it will be TW25B (known in the Marine Corps, where it is used on the up-gunned weapons stations on AAVs as “elephant sperm”). Mad Dog Lab’s XF7 is something else worth looking carefully at, and it appears to work well.

If you prefer to use eye of newt and toe of frog-have at it. My name isn’t attached to any of it, and if you found the absolute key to the cleaning universe, go for it.

My experience over the years as a Marine and a cop and working with sister services, foreign governments, police departments and civilians from all walks of life leads me to some inescapable conclusions.

First is that firearms are machines, and unless you keep them in the safe, heavily lubed, they will exhibit wear. Shocking but true, nothing lasts forever, and the harder you shoot it, the shorter its lifespan. Proper maintenance and cleaning will extend their useful life, but they are going to give up the ghost one day.

Just like you will.

Second is the fact that all guns are no more equal than all people are. The malfunctions that I see at military classes are the result of worn-out guns and bad magazines. In the open enrollment classes, the malfunctions I see are poor quality control on the aftermarket guns, bolt carrier gas keys not staked/staked with a limp wrist, bad magazines and improper lube.

I try not to be shocked and amazed at the poor quality guns being turned out by many, but then the homemade guns-the so-called “FrankenGuns” built with gun show parts and little knowledge-lead me to believe that in the gun world, P.T. Barnum would be a master.

That isn’t to say that all of the companies aren’t capable of turning out good (even great) guns, and often they do. But as a good friend often states, “Even a broken clock is right twice a day.” I’m not impressed with the bleats of “Well, I’ve had this gun for ten years and it has never ‘jammed’ once.” Of course not. Malfunctions only occur when you fire them. I have seen enough of most types to make me realize that the only ARs in my company’s armory are those that meet a standard.

Any gun is a machine, and once in your paws it must be properly maintained. That does not mean incessantly cleaned with obsessive fervor, but rather taking care of those particular areas that affect functioning. Keep a gun book and annotate it with a round count so you can figure out when certain parts (extractor springs, gas rings, bolts and barrels) need replacing. Replace these parts before they replace you.

Keep it lubed to reduce friction, and understand that the more you use it, the more parts need to be replaced. Accept that as a fact of life and drive on.

(Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. Pat is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to various governmental organizations. He can be reached at eag@10-8consulting.com)

By Patrick A. Rogers

S.W.A.T. MAGAZINE – FILTHY 14

Bravo Company Carbine Goes 31,165 Rounds

THE M16 WAS FIRST PROMOTED AS A GUN THAT NEEDED NO MAINTENANCE.

While that statement proved false, a number of factors, including propellant powder and a lack of cleaning supplies and training, led to failures on the battlefield that are still being ballyhooed by muckrakers and the unknowing. They ignore the fact that the M16 is the most accurate and efficient rifle ever used by the military.

However, it is no more a perfect weapon system than the Glock, 1911, M1 rifle or any other rifle, airframe, ship or person.

Much of the noise related to this comes from unrealistic expectations such as the “one shot, one kill” nonsense that used to permeate military training, as well as poor discipline and tactics. Expending six magazines at the cyclic rate when the enemy is 400 meters away and then complaining that your carbine overheated may make headlines, but is also a sign of poor training and leadership.

Additionally, not all ARs are the same. Military weapons are held to a standard and factory Quality Control and outside Quality Assurance mean that problems are minimized.

Aftermarket makers may hold themselves to that same standard or even exceed it… or they can ignore it and substitute below-standard parts.

The latter means that some parts may not meet the mil specification for a number of reasons. This may mean Magnetic Particle Inspection and pressure testing of the bolt and barrel have not been performed, or the type of steel used for the barrel and bolt carrier group (BCG) is not up to spec.

For the average shooter, this may not be an issue. In fact, it may be smart marketing for some makers, as the average AR owner shoots their guns little, if at all.

From my perspective, I don’t aspire to mediocrity. I shoot a lot and stand behind students who are also shooting all day. I prefer to have weapons built to, or exceeding the standard, but also understand that not all users have the same needs or requirements.

But neither do I—not for one New York minute—believe that all ARs are the same.

At my company, E.A.G. Tactical, we are fortunate in that manufacturers regularly provide us with guns in order to see how they perform after a reasonable period of evaluation by students at our classes. While we have written about some for S.W.A.T. Magazine (LMT, S&W, M&P, LWRCI and Colt 6940), others have never seen the pages of this magazine.

Caveat, as we are not carrying these guns for real, we spend little time doing any preventive maintenance. We know that a properly maintained AR will function well. Our purpose here is to see how well the guns will function when left dirty but well lubed. I don’t suggest that you try this at home, especially if you are carrying these guns professionally.

While we used to see a wide variety of guns at class, the quality control of some makes is lacking. Apparently students have been reading the after-action reports on Lightfighter.net and Alumni.net, as we have started to see a swing toward those guns built to (or exceeding) the spec. The net result has been fewer busted guns and more time to better conduct training.

BRAVO COMPANY

Bravo Company USA is a relative newcomer, having entered the market in 2003. Bravo Company MFG was born in 2005 and started producing complete uppers at that time. Bravo Company USA produced a very small number of lowers in 2007, and Bravo Company MFG has been producing lowers since 2008. At this time Bravo Company does not sell complete guns, but several of their dealers do.

Paul Buffoni, the owner of Bravo Company, has built an extremely successful business based on providing quality products with excellent customer service.

We have run a number of Bravo Company guns over the past five years. While most were unremarkable in their boring reliability, one has stood out, both for the longevity of the evaluation period as well as the number of rounds put downrange.

FILTHY 14

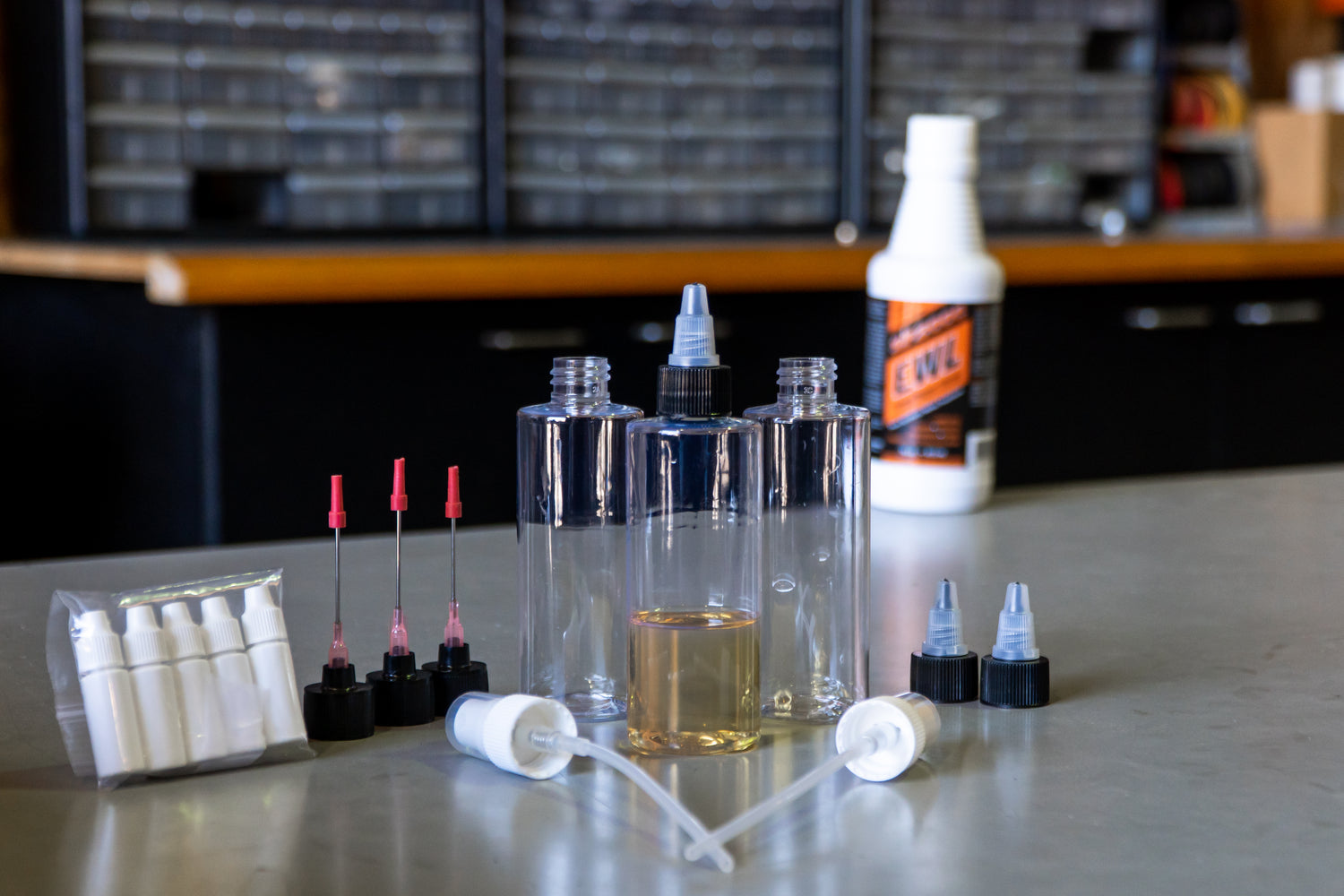

As of this writing, EAG students have 31,165 rounds downrange through Filthy 14. During this evaluation period, it was cleaned once (as in one time), at 26,245 rounds. The end result is that Rack #14 was—and remains—filthy. It is filthy because it has been shot at class. Only at class. Every round that has gone down that barrel has been fired at class, with an average of approximately 1,300 rounds every three days. It has been lubed generously with Slip 2000 Extreme Weapons Lube (EWL).

The combination of carbon and lube create (wait for it)…filth. It is so dirty that, while sitting in the rifle rack, it is almost a biohazard. The filth oozes out and contaminates other carbines adjacent to it.

But it is still shooting—and shooting well.

Rack #14 is a 16-inch Bravo Company Mid Length Carbine—mid length meaning that the gas system is two inches longer than the standard carbine gas system. This permits the use of a nine-inch rail with the standard front sight base. Use of a clamp on the front sight will permit a longer rail to be used.

The longer rail is necessary to accommodate some shooting styles, as well as to provide additional rail estate for the various white lights and IR lasers required to kill bad guys at night.

Subjectively, the mid length system has a softer recoil impulse.

The lower receiver is a Bravo Company USA M4A1, one of very few in circulation. It has a TangoDown BG-16 Pistol Grip. An LMT Sloping Cheekweld Stock (aka the Crane Stock) rides on the milspec receiver extension, as does a TangoDown PR-4 Sling Mount.

The upper is a BCM item, with a milspec 16.1”, 1:7 twist barrel. The barrel steel is chrome moly vanadium (CMV) and certified under milspec Mil-B-11595E.

The BCM bolt is machined from milspec Carpenter 158® gun quality steel, heat-treated per milspec, and then shot peened per Mil-S-13165. Once completed, each bolt is fired with a high-pressure test (HPT) cartridge and then magnetic particle inspected (MPI) in accordance with ASTM E1444.

The handguard is a LaRue 15-9, the nine-inch model to allow full use of the available rail estate.

We have a TangoDown BGV-MK46K Stubby Vertical Foregrip. We use TangoDown BP-4 Rail Panels.

The primary sight is an Aimpoint T1 in a LaRue 660 Mount. The T1 is still on the same set of batteries, and it has never been shut off. The back-up sight is the Magpul MBUS and the sling is the Viking Tactics VTAC.

This is a normal configuration for our guns, although stocks (Magpul CTR, Vltor I-Mod), BUIS (Troy), and day optic (Aimpoint M4s) may be substituted.

IN SERVICE

We received the carbine in late 2008 and put #14 into service shortly thereafter.

At Brady, Texas, in March 2009, it suffered a malfunction, which was reduced with Immediate Action. The bolt was wiped down at 6,450 rounds.

At Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, in May 2009, it had several failures to extract, and the extractor spring was replaced at 13,010 rounds. This is far beyond the normal extractor spring life under these conditions.

At Wamego, Kansas, in June 2009, two bolt lugs broke at 16,400 rounds. We replaced the BCG. Considering the firing schedule, this is within normal parameters.

At Columbus, Ohio, in November 2009, we had several failures to extract at 24,450 rounds. The shooter gave it a field cleaning and replaced the extractor and extractor spring.

At 28,905 rounds, we finally cleaned Filthy 14. As part of our year-end maintenance schedule, we inspect and replace parts as necessary. Filthy 14 looked like the inside of the crankcase of Uncle Ed’s ’49 Packard. It was disgusting to look at and contaminated everything near it, somewhat like the toner cartridges for old printers.

I plopped it into a parts washer filled with Slip 725 parts cleaner, and 20 minutes later it was clean. Mostly clean, anyway.

We have never used a bore brush in the barrel of this gun. We did run a patch down the barrel twice, but that was all. At 50 yards it still shoots two-inch groups, and we understand that it might not at 100 yards and beyond, but we are happy with the fact that, even at 50 yards, the gun is capable of tighter groups than most of the people running it.

We have never used a chamber brush in this gun either. We were often told that this was an absolute must.

Sure…

At the last class in Casa Grande, Arizona, at approximately 30,000 rounds, we had several failures to extract. We replaced the extractor spring and wiped down the BCG.

By the time you read this, we’ll likely have another 3,000 to 4,000 rounds through Filthy 14. At that point we’ll probably retire it. We’ll reuse the LaRue rail, the sights and, after rebuilding the lower, and replace that old and well-worn mid length upper with something else.

Fourteen will continue, but just not as Filthy 14.

WHY WE DID IT

What was the point of this 15-month exercise? We know than an AR built to the spec will run more reliably for a longer period of time than a hobby gun. We have run a number of guns to over 15,000 rounds without cleaning—or malfunctions—as long as they were kept well lubricated. And because we have over 20 Bravo Company guns in the armory, we also understand that the quality of one is not an accident.

My background of belonging to a tribe where weapons cleaning approached Jesuit-like fanaticism caused me to once believe that the AR must be spotlessly, white-glove clean in order for it to run.

We know that is patently false, and in fact the overzealous cleaning regimen—clean for three days in a row, use of scrapers on the BCG, attaching chamber and bore brushes to drills, etc.—is harmful to the guns.

We know that not all ARs are the same, and only a fool believes that “parts are parts.”

If you want something that is visually similar to what the military uses, buy just about anything and you’ll be satisfied. But if you are going to use it for real, buy something that is made to the spec.

Have realistic expectations. No gun—or car, plane, hibachi or person—lasts forever. Recently a customer sent an upper back to Bravo Company complaining that the gas tube was bent.

It sure was. It was bent because the owner apparently fired 600 rounds downrange in full auto, causing the gas tube to melt into the barrel. If you want to be stupid, buy a lesser quality gun and save yourself some money.

Again, let me repeat the caveat. If you are carrying a gun for real, you need to be looking at it every 5,000 rounds or so. But if your cleaning takes more than 10 to 15 minutes, you are wasting your time on nonsense.

At a carbine class in Colorado last year, one-third of the carbines used (eight of 24) were Bravo Company guns. The fact that the Pueblo West classes are populated in large part by professionals means that this may be a clue.

CONCLUSIONS

The fact that Filthy 14 ran so long and well can be attributed to the following:

First is the design of the gun. Cpl. Eugene Stoner knew what he was doing.

Second is the quality of this particular gun from Bravo Company. Paul Buffoni knows what he is doing.

Third is the fact that we used Slip 2000 EWL which, based on past evaluations, keeps guns running long after other lubes have rolled craps. It kept the gun lubricated and made it easier for those rare times when we did clean it. Greg Conner knows what he is doing.

Finally we had a great group of volunteers who took the time to aid us in this evaluation. Bravo Zulu, guys!

(Pat Rogers is a retired Chief Warrant Officer of Marines and a retired NYPD Sergeant. Pat is the owner of E.A.G. Inc., which provides services to various governmental organizations. He can be reached at eag@10-8consulting.com)

By Patrick A. Rogers